How I recorded “The Road Out of Here”

“The Road Out of Here†is inspired by Bob Dylan and Jackson Browne—I think of “Highway 61 Revisited†by the former and “Redneck Friend†from the latter. In style and to some extent theme (one verse is about lyin’ and cheatin’) it’s some kind of Americana, if we think of Americana as including stuff that’s never been done before, like for example the sounds I used on the harps on this song.

The harmonica arrangement for this piece includes four distinct sound setups on the Digitech RP500, playing a variety of parts and roles as the intensity of the arrangement builds. Two harp players could cover just about every part of this arrangement live, provided neither one of them was singing; once the harp gets going, some kind of harp is going until the very last note.

“The Road Out of Here†is a great piece for understanding what this record is all about, because I bring the harmonica layers in one by one throughout the piece, and you can REALLY hear what each layer is adding to the sound of the band. I said in a previous post on the sounds I used on this record that my favorites tend to fall in certain categories: wah, pitch shifted, wobbly, and so on. I use all of those types of sounds, plus some very traditional amped up blues harp, to get the message across on this very intense piece of message-rock.

The Structure of “The Road Out of Hereâ€

“The Road Out of Here†is a 20-bar form; the only chords in the form are I (E), IV (A) and V (B7), but it’s obviously not any kind of standard blues form. The odd-length form is inspired by Dylan, and by my producer Ed Abbiati, both of whom tend to insert phrases of unusual length into their songs. (“It Takes a Lot to Laugh†being the object example in Dylan’s case.) Every iteration of my form is preceded by a 4-8 bar vamp on the tonic chord, which in this case is E, and these vamps are the stage from which I launch each new sound in order. All the harmonica parts are played in second position on a Seydel 1847 in the key of A, and all the harmonica sounds are created with an Audix Fireball V mic into a Digitech RP500 running variations on my patch set for Digitech RP. All but a couple of harp parts were recorded direct to the recording console in the studio via the XLR outputs on the RP500.

Building the arrangement one harp (and verse) at a time

At the beginning of the piece, the bass and drums are vamping by themselves. They’re joined by a harmonica with a heavy amp model, an octave-down pitch shift, and a wah-wah, sounding like some kind of distorted, amped up tenor sax. I recorded that part in the studio live, playing along with John Cunningham on bass and Mark Schrieber on drums. The first vocal verse has occasional support from that instrument; I especially like the part where the chord changes to A and I do a filter sweep with the wah by breathing out on a chord while I slowly push the footpedal down. In general, the wah-wah allows me to make that sound change constantly, because it makes different overtones resonate as I push down on the pedal.

You can hear that on the second verse, where I’m playing a chunky chorded rhythmic figure using the same sound setup; this part was recorded in the same pass as the figure in the intro. The effect here is to make the rhythm part sound like something deeply organic–a bear growling, maybe. This is another example of how the organic quality of breath in the sound of a harmonica is so attention-grabbing and powerful.

On the vamp before the third verse, I introduce the wobbly sound for this piece: a sweeter amp model with a vibrato effect attached. The overall effect is that of a bright 60s-style combo organ like a Vox or Farfisa. With the organic low-octave wah-wahed chugging going on next to it, it’s a very full sound. This part was recorded via overdub in the studio, immediately following the take in which we recorded the rhythm section.

As per my discussion of “Double Lucky,” putting harmonica layers into different octaves is a very useful way to keep them from jamming themselves and everything else up. On “Double Lucky†I used a Low F harp alongside a harp pitched an octave higher. On this piece, the low-pitched harmonica sound is created electronically. I like the electronic approach especially when you want the resulting sound to be somewhat degraded or distorted, or when you’re planning to add even more FX to the sound. In this case, the added effect is a wah-wah, and beginning with a more distorted, lower-pitched sound helps keep the wah wah from pushing the whole thing into feedback.

Help! It’s Godzilla!

The big explosion happens after the third verse, when we hear the opening riff again, and then the words “floor it,†and Godzilla shows up at the party—or at any rate, the biggest block chords ever heard on a harmonica do. The RP500 setup here is one with a Blackface Deluxe Reverb amp model topped off with plenty of gain and a distortion box, run through a Whammy effect with the depth of the whammy set to a major second. With this setup I can play E, D (by shifting the E chord down a whole step), A, and G (by shifting the A chord down) chords on an A harp as massive power chords, and that’s exactly what I do here. I recorded that part as an overdub right after I finished recording the wobble sound.

The section is topped with Mike Brenner’s skyhigh lap steel licks, and a VERY simple harp line (one note, but lots of expression) played through my standard ChampB patch for the RP500 (and every other RP down to the 250), which consists of a Fender Champ amp model coupled with a Fender Bassman 4×10 cabinet model—in other words, a pretty traditional amped-up blues setup. That part was recorded in my home studio with the RP500 functioning as a USB audio interface to the computer.

Everything chills out after that, then rapidly builds back up to a repeat of the big chorded solo. The piece ends with the chorded harmonica blasting away by itself for a half minute or so. I did that specifically to make the point that on the road out of here, harmonica make big, nasty sounds just like everybody else. I recorded an ending like that in the studio when I recorded the chorded stuff, but I redid it in my home studio in order to extend its length. By using the same patch in my home studio that I used in Philly, I was able to get a perfect match on the sound of the original and overdubbed parts.

In performance: Easy with two harp players

There aren’t many places in this arrangement where more than two harp players are playing at once—the exceptions are at the ends of each of the chorded solos, where a traditional amped blues harp sound comes in on top of the chorded harp and the chugging pitch-shifted wah-wahed harp. The traditional lines consist of one note, sometimes bent, sometimes not, so maybe you could hand it off to one of the occasional harp players in the band. (Every band has one, it seems. Most of them can handle playing one note.) Otherwise, you need one harp player to play all the pitch-shifted single note and chugged stuff, and one to cover the wobble sound and the chorded solo.

In case no one remembers, this harp arrangement was previewed in its entirety on this blog when I put up a recording of me playing this song with a looper. It worked with one musician, sounds even better with six.

The sound of this song is so big and tough that it’s easy to think there’s more happening here than a few big, bold harmonica parts. But that’s what’s happening here. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: there’s no reason why there shouldn’t be two harp players in a band instead of two guitarists. Get your friends, get my sounds, and get going.

If you liked that, you’ll like these:

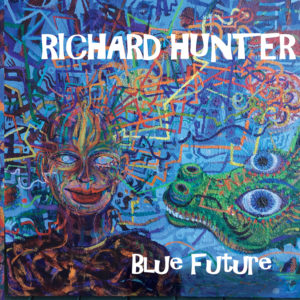

the 21st century blues harmonica manifesto in sound

Get it on Amazon

Get it on iTunes

the rock harmonica masterpiece

Get it on Amazon

Get it on iTunes

Tags In

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

WHAT’S NEW

Categories

- Audio/Video

- Blog

- Blue Future

- Digitech RP Tricks and Tips

- Discography, CDs, Projects, Info, Notes

- Featured Video

- For the Beginner

- Gallery

- Hunter's Effects

- Hunter's Music

- Huntersounds for Fender Mustang

- Meet the Pros

- More Video

- MPH: Maw/Preston/Hunter

- My Three Big Contributions

- Player's Resources

- Pro Tips & Techniques

- Recommended Artists & Recordings

- Recommended Gear

- Recorded Performances

- Reviews, Interviews, Testimonials

- The Lucky One

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Performances

- Zoom G3 Tips and Tricks