How I Recorded “The Lucky One”

I’m planning to do a series of posts describing the specific sounds and techniques I used to record every song on “The Lucky One,” and I thought I’d start out by laying out the overall process that took this record from idea to finished recording.

I recorded “The Lucky One†in two basic stages:

1) With the band in the studio, playing the basic tracks for all the songs.

2) In my home studio, recording harmonica, vocal, piano, and organ parts.

But the story begins before that…

Gearing up for the recording sessions

In February of 2016 I bought a designed-for-purpose music laptop computer by Jim Rosenberry of Studio Cat, with 16 GB of RAM, dual core i7 processor, and a huge screen. I bought this machine specifically so I could work on music anywhere, and it went with me every time I was on the road for more than a week in 2016. Starting in March 2016, working from my home offices in CT and Idaho, I sent frequent rough demos and lyrics of potential selections for the record to my producers Ed Abiatti and Mike Brenner.

I used Cakewalk Sonar running on my laptop and a range of virtual instruments, including EZDrummer 2, VB3 for organ sounds, TruePianos Amber for piano, Lounge Lizard for electric pianos, and Cakewalk Studio Bass to create basic band grooves and arrangements for the songs, and recorded harp and vocal roughs over those to produce the demos. I later used the same instruments in Sonar to record keyboard overdubs, along with vocal and harp overdubs. I used a FocusRite Scarlett 2i2 USB audio interface with an Audio Technica AT4050CM5 large-diaphragm condenser or an ElectroVoice Raven dynamic mic to record vocals, and a Digitech RP500 with an Audix Fireball V mic to record the harp parts.

That collection of instruments and recording gear with that computer was my essential platform throughout the project. It’s portable (though relatively heavy and bulky for a laptop), stable, and extremely powerful. Using Digitech RPs for the harmonica recording interface meant that I could use almost any RP at any location I happened to be at, load the sounds I needed (from my comprehensive patch set for Digitech RP) into it from my computer, and be ready to lay down harp tracks. The computer delivered reliable glitch-free performance, with maximum 10 ms latency in recording mode with the RP500 and under 5 ms with the FocusRite.

Preparing for the sessions

We settled on the songs and arrangements in summer 2016, and I made demos of all the songs in Sonar, packaged those with lyric sheets, and distributed the packages to the band about two and a half weeks before the first recording session.

Beginning on Friday September 16 2016, the band—me on harmonica, Mike Brennan on lap steel, John Cunningham on bass, Mark Schreiber on drums, and Peter Rydberg at the recording console–spent 3 full days and 2 nights in Rydberg’s 1935 Studio in Philadelphia recording the songs. The objective was to get great rhythm section performances and some great jams, and we got everything we wanted. I recorded all harmonica tracks using an Audix Fireball V into a Digitech RP500, with the audio output from the RP500 going to the board via stereo XLR.

Rydberg loaded up the raw tracks from those sessions on a solid state hard drive and sent them to me. I loaded them into Sonar, song by song. Then I got a rough mix going, which was really pretty easy because the tracks basically sounded good with everything set at unity level.

Doing the Overdubs

Then I went to work on the harmonica parts. My goal was to imbue these tracks with color, rhythm, and occasional overwhelming virtuosity. I expected the harmonica tracks to fall in place quickly and easily, and they did. After years spent making and analyzing loop recordings, I have a good sense of how to layer harmonica parts so they don’t interfere with each other or clog up the works. Using pitch shifters to move parts up or down an octave helps a lot. Wah wahs and auto-wahs put motion in parts, and so make them stand out in an arrangement. Wobble sounds like vibrato and rotating speaker convey intense emotion, and work well either in foreground or background of an arrangement.

All overdubbed harp parts were recorded into my laptop via an Audix Fireball V mic into a Digitech RP500, which connected to the computer via USB. (Which means that there was only one stage of audio-to-digital conversion on the overdubs.) One very useful feature of this approach is that if I know what patch was active on the RP when I recorded a part, I can duplicate the sound exactly if I need to for another overdub. It’s worth noting that in the mixing and mastering processes, the only effects applied to the harmonica parts were EQ, delay, and/or reverb—the tones sound very much as they did when they were recorded straight from the RP500.

The last step for me was recording the vocals. For this I used an Audio-Technica AT4050CM5 mic into the preamp on a Focusrite Scarlett 2i2 USB audio interface. I recorded in two different rooms in my house, using blankets and pillows pinned to walls and a portable stand-mounted “vocal booth†to cut down on reflections in the room. In the end, the vocal tracks sounded good, without the wrong kinds of room sounds.

To the Mix

I loaded the overdub tracks as 24-bit 44.1 kHz WAV files into Dropbox, which is where Chris Peet, the mix engineer, picked them up. Chris put his mixes on Dropbox for me to download and audition. This was an efficient way to exchange very large files over very large distances, and it made it easy for everyone to respond quickly to changing arrangements. As it happened, I made some snap decisions about replacing solos recorded with the band in the studio with newer takes, and this process made it easy for everyone to do that. As noted above, the new takes were made using the same RP500 setups as the originals, so they slid right into the mixes with little or no adjustment.

Chris also produced rough mixes for Mike Brenner to use with the percussionist and backup singers (Mark Schrieber and No Good Sister, respectively) in producing their overdubs. Mike sent me the rough mixes from those sessions directly so I could comment on the parts almost as they were recorded. Then those parts too were uploaded to Chris, and the final mixes began.

In the end, it took at least two passes to nail the mix on every song. Some songs went through five passes, with one or two passes per day once the process started. All the mixes were wrapped up in a week of elapsed time.

With the mixes approved, the stuff went to mastering at True East in Nashville. We did three passes on the master, and that was it. The music is recorded.

It was close to a year from start to finish. Would’ve gone faster if I hadn’t had anything else to do at the time, but the proof is in the product, and I like this record plenty. Stay tuned for details on every song, coming to you soon via this blog.

If you liked that, you’ll like these:

the 21st century blues harmonica manifesto in sound

Get it on Amazon

Get it on iTunes

the rock harmonica masterpiece

Get it on Amazon

Get it on iTunes

Tags In

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

WHAT’S NEW

Categories

- Audio/Video

- Blog

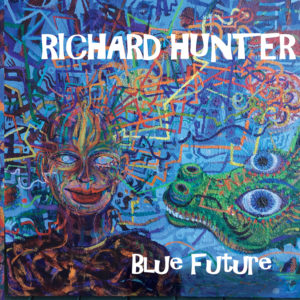

- Blue Future

- Digitech RP Tricks and Tips

- Discography, CDs, Projects, Info, Notes

- Featured Video

- For the Beginner

- Gallery

- Hunter's Effects

- Hunter's Music

- Huntersounds for Fender Mustang

- Meet the Pros

- More Video

- MPH: Maw/Preston/Hunter

- My Three Big Contributions

- Player's Resources

- Pro Tips & Techniques

- Recommended Artists & Recordings

- Recommended Gear

- Recorded Performances

- Reviews, Interviews, Testimonials

- The Lucky One

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Performances

- Zoom G3 Tips and Tricks